Defining Value Stocks

What is a Value Stock?

A value stock is typically characterized by a trading price that is lower than what its performance metrics suggest. Investors find value stocks appealing due to their potential to correct to a higher price, reflecting the company’s fundamental worth over time. Common attributes of value stocks include high dividend yields, low price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, and low price-to-book (P/B) ratios. They are often seen as financially robust companies with stable earnings and lower market price volatility. Essentially, these stocks are undervalued by the market, offering a promising opportunity for investors to buy shares at a discount.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Low-Priced Relative to Financial Performance: Value stocks are shares of publicly traded companies that trade at lower valuations compared to their earnings and long-term growth potential. This means they are priced more affordably in relation to their financial metrics, presenting potential investment value.

- Investment Advantage During Market Downturns: When the stock market experiences an overall decline, even well-established and fundamentally strong companies see a drop in share prices. Investing in value stocks during such times can be particularly advantageous as it provides an opportunity to acquire quality stocks at reduced prices.

- Potential for Maximized Long-Term Returns: Value investing focuses on buying stocks that seem undervalued, akin to purchasing $100 bills for $80. This strategy often targets established companies with a track record of stability. Consequently, it holds the potential for considerable upside and maximized long-term investment returns.

Key Characteristics of Value Stocks

Value stocks exhibit specific characteristics that can make them attractive to certain investors. These traits differentiate them from growth stocks, allowing investors to identify potential investments.

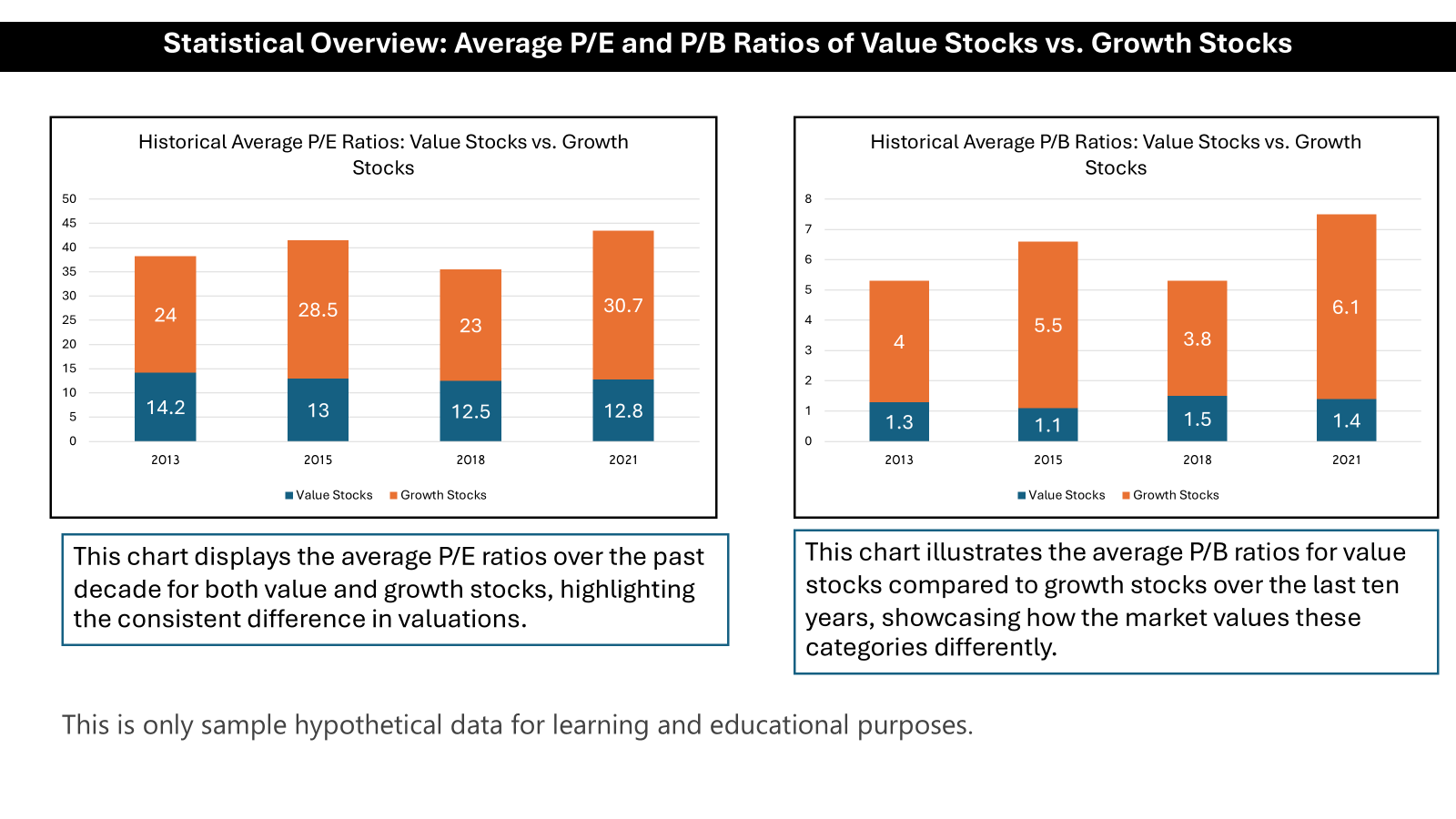

- Low Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio: Value stocks often trade at lower P/E ratios, indicating that the market prices them lower relative to their earnings. This can be a sign that the stock is undervalued.

- Low Price-to-Book (P/B) Ratio: These stocks frequently have a lower market price compared to the company’s book value, suggesting a potential undervaluation.

- Consistent Dividends: Many value stocks belong to mature companies that distribute regular dividends, providing income while holding the stock.

- Stable Business Models: Companies offering value stocks typically have established, stable business models, minimizing risk compared to emerging growth sectors.

- Lower Growth Expectations: While value stocks may not promise rapid growth, they generally come from companies with reliable, slow, and steady growth rates.

Recognizing these characteristics can help investors spot potential value stocks and capitalize on their potential for market correction and long-term appreciation.

Historical Overview of Value Investing

Early Predecessors and Evolution

The concept of value investing dates back centuries, with roots in observations and practices that predated modern financial markets. As early as the 1600s, the intrinsic value of equities was recognized, laying the groundwork for understanding market inefficiencies. For instance, Daniel Defoe noted the inflated trading prices of the East India Company’s stock in the 1690s, suggesting market prices did not always reflect intrinsic value.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, figures like Hetty Green emerged as pioneers in value investing. Often deemed “America’s first value investor,” Green capitalized on purchasing undervalued assets and patiently waiting for market reassessment

The 1920s saw the formal evolution of value investing with the contributions of Forest Berwind “Bill” Tweedy, founder of the oldest value investing firm on Wall Street, Tweedy, Browne. Tweedy capitalized on acquiring smaller, less liquid family-owned companies at significant discounts, focusing on their book value. This practice flourished through his collaboration with Benjamin Graham, furthering value investing’s popularity

John Maynard Keynes also contributed to the evolution of value investing by adopting a more intrinsic value-focusedapproach after initial challenges with market timing. His successful management of the King’s College endowment in the 1920s marked a turning point, demonstrating the efficacy of investing based on fundamental value rather than speculative timing.

Throughout the 20th century, these early methods and philosophies laid the foundation for modern value investing, inspiring future investors to seek undervalued stocks with robust fundamentals. The evolution of value investing has underscored the importance of understanding market inefficiencies and recognizing the intrinsic value of investments. This disciplined approach to investing continues to be a cornerstone strategy for investors worldwide.

Well-Known Value Investors

A few renowned individuals have significantly shaped the world of value investing, each contributing to its popularization and refinement.

Warren Buffett, perhaps the most famous value investor, built his career on the principles he learned from his mentor, Benjamin Graham. Buffett’s approach, centered on buying quality companies at discounted prices, has yielded incredible returns for Berkshire Hathaway, demonstrating the power of value investing.

Benjamin Graham, often credited as the father of value investing, laid the theoretical groundwork with his seminal books, “The Intelligent Investor” and “Security Analysis.” His focus on intrinsic value and margin of safety has become the bedrock of value investing strategies.

Charlie Munger, Buffett’s long-time business partner, is another prominent advocate of value investing, emphasizing the importance of multidisciplinary thinking and patience. His approach blends Graham’s principles with his own deep understanding of business acquisition and management.

Seth Klarman, a contemporary value investor, is known for his disciplined approach and is often cited for blending value investing principles with deep analysis. His book, “Margin of Safety,” is highly regarded among investors, despite its limited availability.

Lastly, Walter Schloss, a discipleof Graham, proved through his independent fund, Walter J. Schloss Associates, that small-scale investors could consistently beat the market by adhering to value investing principles. With a no-frills approach focused on low-risk investments, Schloss demonstrated that a deep understanding of a company’s intrinsic value could yield substantial long-term rewards

These investors, among others, have collectively contributed to the strong foundations of value investing, inspiring countless individuals to adopt a patient, analytical approach to recognizing undervalued opportunities in financial markets.

Valuation Metrics for Value Stocks

Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio Explained

The Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio is a fundamental valuation metric used to assess whether a stock is over or undervalued relative to its earnings. The P/E ratio is calculated by dividing a company’s current stock price by its earnings per share (EPS). For example, if a stock is priced at $20 and its EPS is $2, the P/E ratio would be 10.

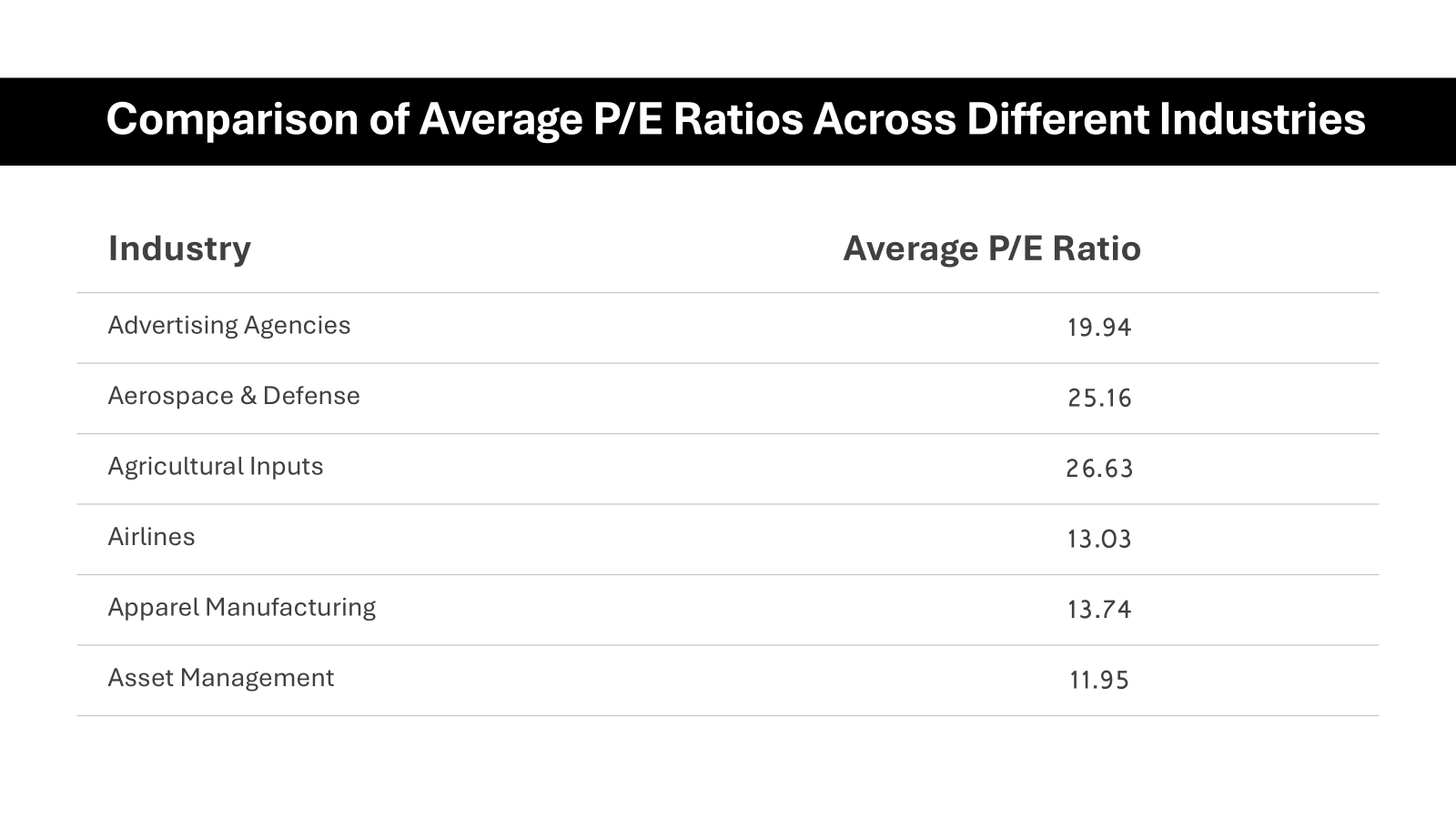

This ratio gives investors insight into how much they are paying for each dollar of earnings. A high P/E ratio may suggest that investors expect higher earnings growth in the future compared to companies with a lower P/E ratio. Conversely, a low P/E might indicate that the stock is undervalued or that the company is experiencing difficulties.

Investors should consider both historical and forward P/E ratios. Historical P/E examines the relationship between current prices and past earnings, while the forward P/E anticipates upcoming earnings changes. Despite its utility, the P/E ratio should not be used in isolation; it is most effective when combined with other metrics to form a comprehensive investment evaluation strategy. By doing so, investors can better gauge a stock’s inherent value and potential for future growth.

Understanding the Price-to-Book (P/B) Ratio

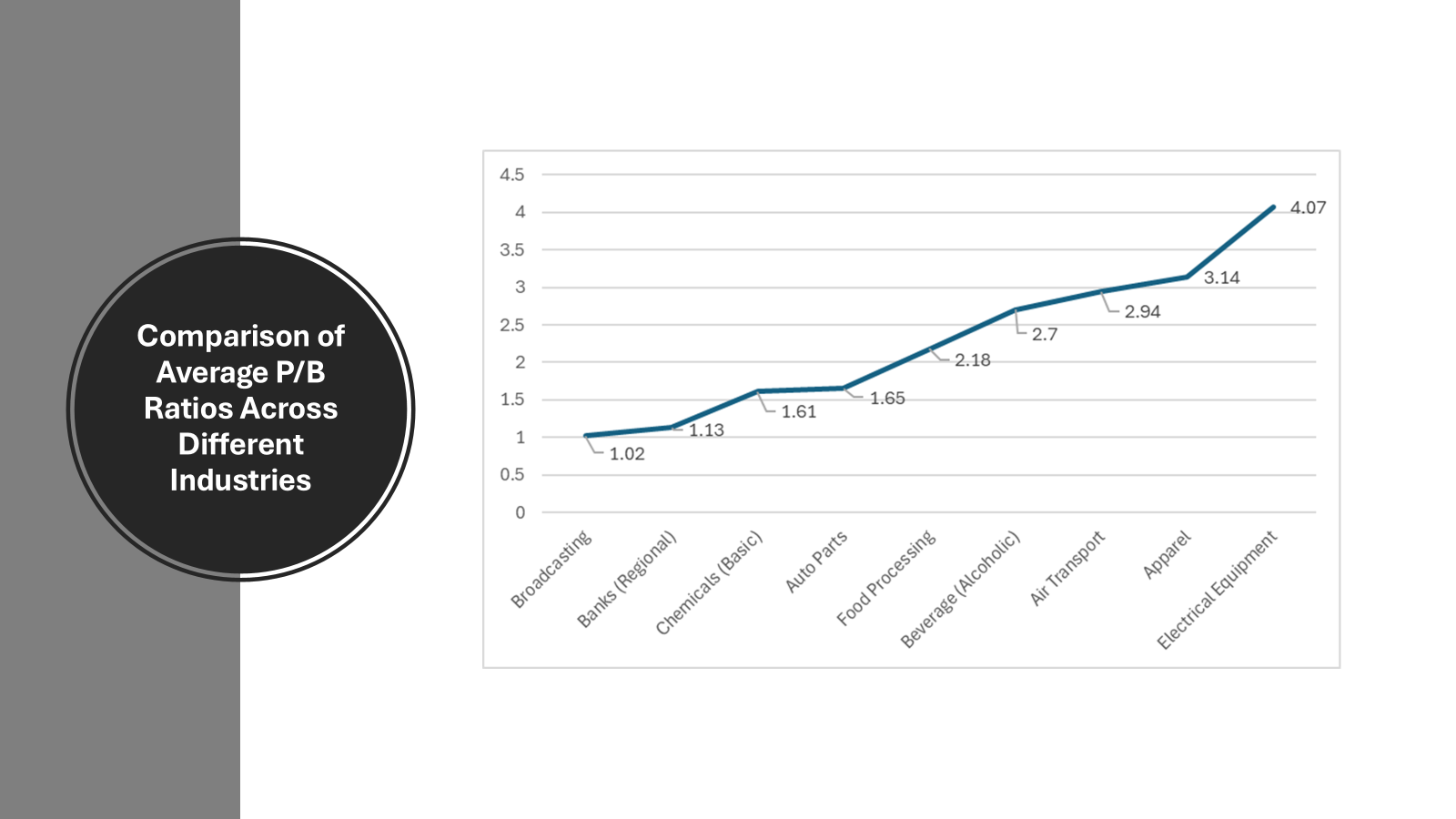

The Price-to-Book (P/B) ratio is a crucial tool for value investors, offering a snapshot of how the market values a company’s net assets. It is calculated by dividing a company’s stock price by its book value per share. The book value refers to the net difference between a company’s total assets and its liabilities, essentially representing the intrinsic net worth from an accounting perspective.

A low P/B ratio can point towards a stock being undervalued, which suggests that the market price is either at or below the reasonable valuation of the company’s assets . For instance, a P/B ratio below 1.0 implies that the market perceives the company’s assets to be worth less than their recorded purchase value, potentially indicating an overlooked investment opportunity.

However, it is vital to consider that different industries have varying benchmarks for what is considered a healthy P/B ratio. Asset-heavy industries, such as manufacturing, might typically exhibit lower P/B ratios compared to software or tech companies. Therefore, comparing a company’s P/B ratio against industry averages can provide investors with a more contextual understanding.

While the P/B ratio is a powerful indicator of potential undervaluation, investors should be cautious. A low P/B ratio could alsosignal fundamental issues within the company, such as declining asset value or poor management effectiveness. Therefore, it’s crucial to integrate the P/B ratio with other metrics and quality assessments for a rounded evaluation of potential investments. This helps ensure that investors can discern whether a low P/B ratio truly represents a hidden value or is merely indicative of deeper systemic challenges.

Other Important Metrics: EV to EBITDA, PEG Ratio

Apart from the commonly used P/E and P/B ratios, other metrics like EV to EBITDA and the PEG ratio provide deeper insights into evaluating stocks, especially in diverse market conditions.

The EV to EBITDA ratio compares a company’s Enterprise Value (EV) to its Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBITDA). EV includes market capitalization and net debt, offering a comprehensive perspective of a company’s valuation. The EV to EBITDA ratio is particularly useful for comparing companies with differing capital structures, as it eliminates the effects of financial leverage and depreciation, offering a clearer picture of a company’s operational efficiency. A lower ratio could suggest that a company is undervalued relative to its earnings potential.

The PEG (Price/Earnings to Growth) ratio adjusts the P/E ratio by incorporating the company’s earnings growth rate, making it a more dynamic metric. It is calculated by dividing the P/E ratio by the earnings growth rate. The PEG ratio allows investors to compare stocks with different growth projections, providing insight into whether a stock’s market price justifies its expected growth. A PEG ratio of less than 1.0 often indicates undervaluation relative to growth, marking it as a potential investment opportunity. Both EV to EBITDA and the PEG ratio offer nuanced evaluations, helping investors to look beyond traditional metrics. While these ratios enhance understanding, they are most effective when considered alongside other factors, such as industry dynamics and market conditions, to make informed investment decisions.

The Appeal of Value Stocks

Reasons for Undervaluation

Stocks may become undervalued for a myriad of reasons, creating potential opportunities for astute investors. One common cause is market sentiment and investor mood. Stocks can be affected by adverse news or investor pessimism about a specific industry or market, which might not necessarily reflect the company’s actual financial health. This disconnect can present discounted buying opportunities.

Economic downturns also play a role in undervaluation. During recessions or periods of economic instability, stock prices may fall as a reflection of broader market fears, often dipping below their intrinsic value. This can be especially true for cyclical industries where business performance is closely tied to economic cycles, such as the airline or automotive sectors.

Additionally, a company might be undervalued due to being underfollowed or having less investor awareness, particularly if it operates in niche or emerging markets. Analysts and investors may overlook these stocks in favor of more popular or high-profile companies, leading to undervaluation despite strong fundamentals.

Lastly, internal challenges such as managerial issues, legal disputes, or earning surprises can temporarily depress stock prices. If these issues are rectifiable, they may provide a point of entry for value investors seeking long-term growthpotential. Recognizing these underlying reasons can thus aid investors in identifying genuinely undervalued stocks, leveraging temporary setbacks, or market inefficiencies to their advantage.

Hedge Against Market Downturns

Value stocks serve as an effective hedge against market downturns due to their inherent characteristics. Often found in defensive sectors like utilities, consumer staples, and healthcare, value stocks tend to exhibit more stability during economic uncertainties. These sectors typically provide essential goods and services, ensuring steady demand even amid economic slowdowns.

The lower volatility of value stocks is a key factor in their resilience. Because they generally trade below their intrinsic value, they are less susceptible to drastic market corrections that can affect overvalued growth stocks. Moreover, the stable earnings and dividends associated with many value stocks provide a cushioning effect, offering income and reducing the impact of market fluctuations.

Investors also often view value stocks as “safer” options during economic strife. This perception can lead to increased demand for value stocks, further buffering them against steep declines seen in the broader market. By diversifying a portfolio with value stocks, investors can mitigate risk and enhance the durability of their investments during turbulent market conditions, providing a protective layer against significant losses.

Potential for Long-term Growth

Value stocks present a significant potential for long-term growth by capitalizing on market inefficiencies. As these stocks are often undervalued, they have the room to appreciate over time when the market eventually recognizes their true worth. Investors who patiently hold value stocks can benefit from both capital appreciation and dividend yields, resulting in a compounded growth effect over the years.

Many value stocks belong to mature companies with established business models and a track record of consistent earnings. These attributes can contribute to sustained growth over time, particularly as the companies continue to innovate and optimize their operations to improve profitability.

Additionally, the reinvestment of dividends can significantly boost the overall return on investment. Constant dividend payouts allow investors to reinvest income back into the stock or diversify into new holdings, enhancing the long-term growth potential of their investment strategy.

The combination of these elements makes value stocks appealing for investors focused on long-term wealth accumulation, balancing stability with the potential for appreciation once the market adjusts to recognize the intrinsic value.

Examples of Value Stocks

Classic Value Stock Case Studies

Classic value stock case studies demonstrate the power of disciplined investing in undervalued opportunities. One notable example is Berkshire Hathaway, initially a struggling textile company when Warren Buffett took control in the 1960s. Through strategic acquisitions and focusing on intrinsic value, Buffett transformed it into a diversified conglomerate, yielding unparalleled returns for investors over decades.

Another classic case is Coca-Cola, which in the 1980s, was undervalued due to market skepticism about the soft drink industry’s growth prospects. Warren Buffett’s investment in Coca-Cola capitalized on its brand strength, distribution networks, and global market share. This investment is now considered one of the most successful examples of value investing.

More recently, Cisco Systems, following the tech bubble burst in the early 2000s, provides a modern case of a value investment. Despite significant dips in stock prices, Cisco maintained robust fundamentals, including cash reserves and strong market presence in the networking hardware industry, allowing it to rebound and deliver consistent growth.

These examples underscore the potential profitability of identifying undervalued stocks with strong fundamentals and the visionary management needed to leverage market adjustments for long-term shareholder value. Analyzing these case studies offers valuable lessons for investors seeking to navigate the complexities of value investing and find opportunities that may not be immediately apparent to the broader market.

Comparing with Growth Stocks

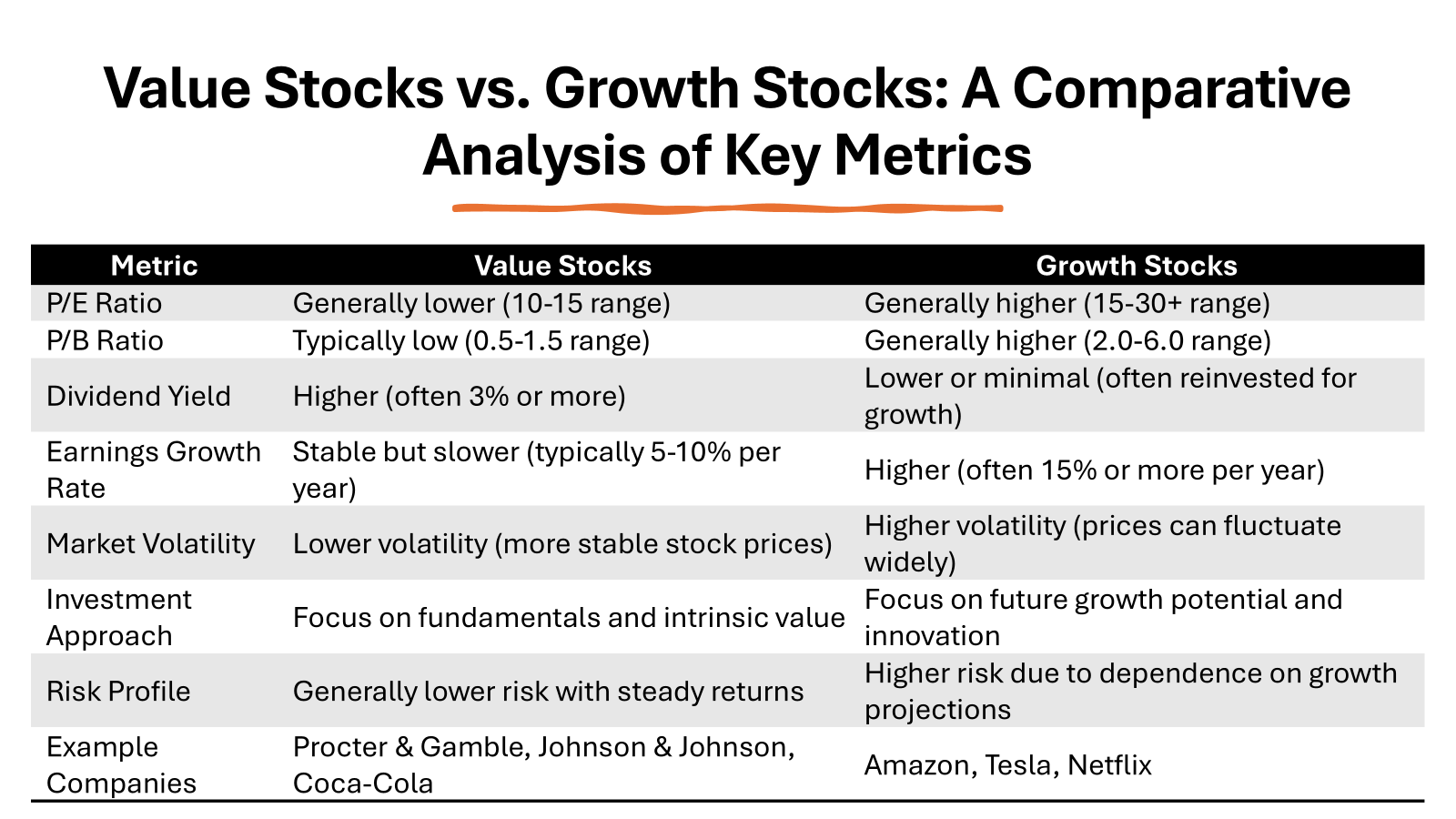

Value stocks and growth stocks represent two distinct investment styles, each offering unique opportunities and challenges. The fundamental difference lies in their valuation and expected performance outlook.

Value stocks are typically identified by their lower price-to-earnings and price-to-book ratios. They belong to companies perceived as undervalued by the market, often reflecting mature, stable businesses with consistent dividends. Investors looking for reliability and income often favor value stocks, believing these stocks will rebound as the market corrects inefficiencies in valuation.

On the other hand, growth stocks are associated with companies showing higher potential for expansion and revenue increase. Despite usually having higher valuations and trading at elevated multiples, such as P/E ratios, growth stocks attract investors willing to accept higher volatility in pursuit of substantial price appreciation. Companies in technology or biotech sectors often fall into this category, driven by innovation and market disruption.

While value stocks are perceived as safer with dividends offering steady returns, growth stocks can offer substantial returns in thriving markets, albeit with higher risk during economic downturns. The decision between investing in value or growth stocks depends on individual risk tolerance, investment goals, and economic outlook, with many investors diversifying across both to optimize portfolio balance.

In summary, the choice between value and growth stocks requires careful consideration of the investor’s objectives and the prevailing economic conditions, with each category offering different paths to potential rewards. By understanding these differences, investors can make informed decisions that align with their financial strategies and risk preferences.

Strategies for Investing in Value Stocks

How to Identify a Value Stock

Identifying a value stock involves a systematic approach to evaluating a company’s financial health and market position. Here are key steps and factors to consider:

- Examine Financial Ratios: Start with fundamental valuation metrics such as the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, price-to-book (P/B) ratio, and dividend yield. A lower P/E ratio compared to industry peers could indicate potential undervaluation. Similarly, a P/B ratio below 1.0 may suggest that the stock is trading below its book value.

- Analyze Earnings Stability: Assess the company’s earnings history to determine consistency and growth potential. Companies with a strong track record of stable or increasing earnings are often more attractive as value investments.

- Evaluate Company Fundamentals: Review the balance sheet for strong financial positions, low debt levels, and positive cash flows. Financial health is crucial for sustaining value and growth.

- Industry Context: Compare the company’s valuation with its industry competitors. A stock may appear undervalued due to specific industry trends, creating relative opportunities.

- Assess Management and Strategy: Strong, competent leadership with a clear strategy can enhance a company’s potential to overcome market challenges and increase shareholder value overtime. Evaluating the track record and strategic vision of the management team can provide insights into future performance.

- Consider Market Perceptions: Sometimes stocks are undervalued due to temporary market pessimism or overlooked qualities. Understanding market sentiment and its potential for reversal can guide buying decisions.

By integrating these steps into your stock selection routine, you can effectively identify value stocks that offer potential for future appreciation and income generation, aligning with consistent investment strategies. Taking into account diverse indicators ensures a comprehensive understanding, enabling informed decisions rather than relying on a single metric or trend.

Common Value Investing Strategies

Value investing encompasses a range of strategies that cater to different aspects of undervaluation and financial health. Below are some of the most common approaches used by investors to identify and capitalize on value stocks:

- Deep Value Investing: This strategy involves seeking stocks significantly undervalued relative to their intrinsic worth. Investors focus on buying businesses trading below their book value or with very low price multiples. The aim is to exploit extreme mispricing in the market.

- Dividend Yield Approach: Investors following this method prioritize companies that pay high, sustainable dividends. Stocks offering higher-than-average yields may signal undervaluation and provide steady income, aligning with long-term investment horizons.

- Contrarian Investing: Contrarians buy stocks that are currently out of favor with the market but show a promising turnaround potential. This approach requires patience and a deep understanding of the underlying business to wait out temporary challenges.

- Quality Value Investing: Focusing on companies with strong fundamentals, stable cash flows, and a competitive edge, this strategy seeks value stocks that also demonstrate quality characteristics. Investors look beyond merely low valuations to include business resilience and performance metrics.

- Relative Value Analysis: This strategy involves comparing the valuations of companies within the same industry to identify undervalued stocks. By analyzing metrics such as P/E, P/B, and EV/EBITDA ratios against peers, investors aim to pinpoint potential value opportunities among similar businesses.

Each of these strategies offers unique paths to uncovering value stocks, allowing investors to tailor their approach based on risk tolerance, market understanding, and investment goals. Successful value investing often involves blending these methods, continuously assessing industry conditions, and maintaining a keen eye on emerging market trends. By doing so, investors can make informed and strategic decisions to capture long-term gains and minimize risks.

Contrarian and Margin of Safety Approaches

The contrarian approach in value investing is centered on defying prevailing market sentiments. Contrarian investors actively seek out stocks that are overlooked or even abandoned by the market, believing that the broader consensus often misinterprets temporary challenges as insurmountable declines. These investors take advantage of pessimistic outlooks, identifying undervalued stocks poised for recovery when broader perceptions align with the company’s intrinsic value. Their success hinges on comprehensive research and patience, often waiting for market corrections to realize potential gains.

The margin of safety approach, popularized by Benjamin Graham, involves investing in stocks priced well below their calculated intrinsic value. This strategy protects investors against errors in valuation or unexpected market volatility by providing a cushion, hence the ‘safety margin.’ By purchasing stocks with a significant margin of safety, investors reduce downside risks and increase the probability of positive outcomes when the stock’s market value corrects over time. It’s a disciplined approach that requires careful calculation of a company’s intrinsic value using detailed financial analyses and forecasts.

Both approaches share the ultimate goal of capitalizing on stock misvaluations, but they do so through different lenses. While contrarian investing might focus more on sentiment and timing, the margin of safetyapproach emphasizes precision in valuation and risk management. Together, these strategies offer a well-rounded framework for identifying and investing in value stocks, protecting investors from potential risks while maximizing the opportunity for growth. Balancing these approaches enables investors to navigate market complexities, seeking value even when others might see volatility or uncertainty.

Risks and Criticisms

Potential Risks with Value Stock Investing

Investing in value stocks carries its own set of risks, which investors should carefully evaluate before committing capital. One of the main risks is the potential misidentification of a value stock. A stock that appears undervalued might actually be a “value trap,” where the low price is justified by deteriorating fundamentals or industry challenges. This misjudgment can lead to investments in companies that fail to recover, resulting in financial losses.

Another significant risk involves industry cyclicality and economic dependency. Many value stocks belong to sectors that are highly dependent on economic cycles. During downturns, these stocks can experience further declines, undermining their supposed undervaluation. Investors need to assess macroeconomic trends and sectoral dynamics to better predict potential pitfalls.

Moreover, the time horizon required for value stocks to realize their potential might be longer than expected. The market might take considerable time to re-evaluate a company’s true worth, requiring patience and long-term commitment from investors who may not see immediate returns.

Unforeseen internal challenges, such as management failures, accounting discrepancies, or strategic missteps, pose another risk. Such problems can hinder a company’s ability to realize its intrinsic value despite initially attractive valuations.

Additionally, there is always the inherent risk of broader market conditions shifting. External economic factors such as interest rate changes, inflation, or geopolitical tensions can impact the market perception of value stocks, exacerbating volatility or delaying recovery.

Being aware of these risks allows investors to make informed decisions, incorporating thorough research and diversified strategies to mitigate potential downsides. The key is a balanced approach that combines risk assessment with the pursuit of undervalued opportunities.

Over-simplification and Market Expectations

One of the primary criticisms of value investing revolves around the potential for over-simplification. At its core, value investing relies heavily on quantitative metrics such as P/E and P/B ratios to identify undervalued stocks. However, focusing solely on these numbers can lead investors to overlook qualitative factors that might affect a company’s future performance, such as market trends, consumer behavior, or emerging competition.

Market expectations can further complicate the picture. Stocks that appear undervalued may actually be priced accurately by the market, taking into account slower growth prospects or significant operational challenges that are not apparent in the financial statements alone. As a result, relying strictly on traditional valuation metrics might lead to investments in companies that are cheap for a reason, without considering the inherent risks or the company’s strategic position.

Moreover, the dynamic nature of markets means that expectations are often ephemeral and can change rapidly. Investors need to consider how shifting expectations might impact the perceived value of a stock, staying updated with economic trends and industry developments. This broader perspective is crucial to avoid falling into the trap of viewing value investing as a simplistic formula without acknowledging the multifaceted nature of market performance.

To mitigate these challenges,investors should incorporate a holistic approach that balances quantitative analysis with a deep understanding of qualitative factors. This involves regularly revisiting assumptions, staying informed about industry dynamics, and maintaining flexibility to adjust strategies as the market landscape evolves. By doing so, investors can avoid the pitfalls of over-simplification and align their expectations more closely with reality, enhancing the potential for successful value investing.

Conclusion

A value stock is a type of equity that is considered to be undervalued in the marketplace. Investors look for these stocks because they believe the stock’s intrinsic value is higher than its current trading price, offering a potential bargain. The criteria for identifying value stocks often include low price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, low price-to-book (P/B) ratios, and other fundamental metrics that suggest the stock is trading below its true value. Companies like Walt Disney, despite their premium brand, can sometimes be considered value stocks if their market price does not reflect their long-term potential.

Investors seeking value stocks often rely on detailed analysis and data from sources like Morningstar and government data to make informed decisions. They look for companies with strong fundamentals, such as consistent earnings, solid dividends, and good management. These stocks are often found in sectors that are out of favor with the market, making them hidden gems. For instance, retail companies might be overlooked during economic downturns, presenting opportunities for value investors.

The concept of value investing was popularized by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, and it remains a cornerstone of many investment strategies today. Value stocks are seen as having the potential for significant upside, especially when the market corrects itself and the stock’s price aligns with its intrinsic value. This approach requires patience and a long-term perspective, as the market may take time to recognize the stock’s true worth.

In summary, value stocks offer investors the chance to buy high-quality companies at a bargain price. By focusing on fundamental analysis and looking beyond short-term market fluctuations, investors can identify stocks that are poised for outperformance. This strategy is not without risks, but with careful research and a disciplined approach, value investing can be a rewarding way to build a diversified portfolio.

FAQs

What defines a value firm?

A value firm is typically defined by its stock trading at a lower price relative to its fundamentals, such as earnings, dividends, or book value. These companies often showcase stable earnings, offer consistent dividends, and have robust financial health, yet are undervalued by the market. They are usually identified through low price-to-earnings (P/E) and price-to-book (P/B) ratios, signaling potential for market correction and long-term appreciation.

What differentiates value stocks from growth stocks?

Value stocks are typically undervalued based on fundamentals and are often mature companies with consistent earnings and dividends. Growth stocks, on the other hand, are from companies expected to have higher-than-average revenue growth, often reinvesting profits rather than paying dividends. While value stocks are seen as stable with lower risk, growth stocks are perceived as having high potential but with increased volatility.

Are value stocks a good investment for beginners?

Yes, value stocks can be a good investment for beginners due to their generally lower risk and potential for steady returns. They often belong to established companies with stable financials, offering dividends for consistent income. Beginners benefit from the relative predictability and the learning opportunity value stocks provide in understanding market fundamentals and valuation metrics.

What are some examples of well-known value investors?

Famous value investors include Warren Buffett, known for his long-term investment strategy and successful leadership at Berkshire Hathaway. Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, is celebrated for his influential books on the subject. Other notable value investors are Charlie Munger, Buffett’s partner, and Seth Klarman, author of “Margin of Safety.” Each has significantly contributed to the field with their unique approaches and insights.

How do you calculate the intrinsic value of a stock?

Calculating the intrinsic value of a stock typically involves discounting future cash flows to present value. You can use models like the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis, where expected future cash flows are estimated and discounted using a rate that reflects the investment’s risk. Another method is using valuation metrics such as the P/E ratio, adjusted for growth, to determine a fair price aligned with the company’s fundamentals and market position.

How do high value stocks perform compared to other stocks?

High value stocks often provide more consistent returns compared to high-growth stocks, offering stability and regular dividends. They tend to perform well in market downturns due to their lower volatility. Over the long term, value stocks can outperform the market by correcting initial undervaluation. However, they generally offer less explosive growth potential than growth stocks in bullish markets.