Importance of Amortization in Business Accounting

In the business world, amortization isn’t just important; it’s a financial compass. It aids in pinpointing the true value of intangible assets over time, which could include things like patents, trademarks, Copyright or even goodwill from a recent acquisition. This is vital when assessing the health and potential of a business, especially during strategic moves like mergers or investments.

Furthermore, it allows for a more accurate forecast of future costs. Knowing how much of each loan payment goes towards interest and principal helps in tax deductions and planning cash flow. It’s a way of showing how a company gradually consumes the benefits of its intangible assets, and this gradual allocation of cost over an asset’s useful life can significantly impact the bottom line by reducing taxable income and shaping the portrayal of a company’s profitability to investors.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Use straight-line amortization to allocate the cost of an intangible asset evenly over its useful life. This method involves dividing the asset’s initial cost or Capital Expenditure by its estimated useful life to determine a constant annual amortization expense.

- Regularly review and adjust the amortization schedule to reflect any changes in the asset’s expected use or production levels. Compare the forecasted amortization with the asset’s actual usage and update the life expectancy or residual value estimates as necessary.

- Consider alternative amortization methods for assets whose benefit is more closely tied to production levels. Calculate the amortization expense based on the actual usage or the number of units produced, ensuring that the expense matches the asset’s consumption more accurately.

The Anatomy of Amortization in Accounting

Understanding the Types of Amortizable Assets

If you’re diving into the world of amortization, you’ll quickly find that not all assets get the same treatment. Only non-physical assets, or intangible assets, have the privilege—or obligation—of being amortized. Imagine things you can’t touch but hold value like a secret recipe, brand reputation, or the legal right to produce a certain product for a period, also known as patents.

A common feature of these assets is that they offer benefits to the business over multiple periods. While a patent might expire after 20 years, a trademark could potentially serve the company indefinitely if renewed periodically. Hence, assets with a defined life span are systematically amortized over said duration, spreading the initial costs across their useful lives in a fair and orderly manner.

A contra-asset account, typically titled “Accumulated Amortization,” is used to track the total amortization expense recognized to date.

Key Distinctions: Amortization vs. Depreciation

When grappling with the concepts of amortization and depreciation, think of the former as dealing with the unseen and the latter with the physical. Amortization is the financial practice used for intangible assets, those elusive non-physical assets that contribute to a business’s value—like intellectual property or licenses. These items are amortized since they have a clear useful life but no physical presence.

Depreciation, on the other hand, is all about tangible assets: the office buildings, machinery, or company vehicles. These assets deteriorate over time due to usage and wear, hence their value depreciates. One key difference also lies in the salvage value; depreciated items often assume a value at the end of their life, unlike intangible assets that typically don’t hold a salvage value post-amortization.

Next, the amortization expense is added back on the cash flow statement in the cash from operations section, just like depreciation Expense.

Mastering the Calculation of Amortization Expense

Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating Amortization

Calculating amortization doesn’t have to be as daunting as it sounds! To simplify, you’ll start with the cost of your intangible asset and then subtract any residual value it might have after its useful life (though most intangible assets don’t have residual value). You’ll spread the remaining cost evenly over the asset’s estimated useful life. Here’s a breakdown:

- Identify the initial cost of the intangible asset.

- Determine the useful life of the asset (how long it will contribute to revenue).

- Subtract any residual value the asset may have at the end of its useful life.

- Divide the adjusted cost by the number of years in the useful life to find the annual amortization expense.

- Record the expense each year until the end of the asset’s useful life.

For example, if you purchase a patent for $50,000 with a useful life of 10 years and no expected residual value, you’d divvy up that $50,000 over 10 years, resulting in yearly amortization expenses of $5,000. Easy as pie!

Real-World Examples of Amortization Calculations

Seeing amortization in action can help you grasp the concept better. Take a mortgage, for instance. If someone takes a $200,000 mortgage loan for 20 years at a 5% annual interest rate, they make a monthly payment of $1,073. This payment includes both interest and principal repayment. Initially, the interest portion is higher, but as the outstanding principal decreases, so does the interest, and the principal portion becomes larger.

Another example involves business assets. Suppose a company buys a patent for $180,000 that lasts for 20 years. The cost of acquiring the patent, say another $20,000 for legal fees, is also factored in, bringing the total to $200,000. This cost is then amortized over the life of the patent, leading to an annual amortization expense of $10,000. Hence, the company would report this amount as an expense on its income statement every year, reducing both its taxable income and the reported net income.

The Role of Amortization Schedules

Crafting a Comprehensive Amortization Schedule

Creating a comprehensive mortgage amortization schedule gives a clear, detailed picture of how each payment affects the loan balance over time. Here’s how you can create one:

- Begin by identifying the total amount of the loan or the cost of the intangible asset.

- Determine the interest rate, the time frame for the loan or asset’s useful life, and the payment frequency.

- Calculate the periodic payment amount using a standard amortization formula or an online calculator.

- Construct a table starting with the initial loan balance or asset cost.

- For each period, calculate and note the amount of payment that goes toward interest based on the current balance.

- Subtract the interest from the total payment to find the principal portion.

- Deduct the principal paid from the outstanding loan balance to find the new balance.

- Repeat the process for each payment period until the balance reaches zero.

This table not only helps in tracking payments but also is instrumental for forecasting financial obligations and making well-informed decisions about prepayments or refinancing.

If a borrower refinances the loan, makes extra payments, or misses payments, the original amortization schedule is modified.

Reading and Interpreting Amortization Tables

Reading and interpreting amortization tables is akin to following a roadmap through the lifecycle of a loan or asset. Here’s the rundown:

- Payment Number: This shows where you are in the sequence of payments.

- Beginning Balance: The debt owed at the start of the period.

- Scheduled Payment: The fixed amount you pay in that period.

- Principal: The bit of your payment that knocks down the original amount you borrowed.

- Interest: The cost you’re covering to borrow the money, which naturally decreases as the principal is paid off.

- Ending Balance: What you still owe after this payment.

Want to know how much interest you’ll pay over the life of the loan or how principal payments affect your interest charges? Look no further; the amortization table lays it all out. It’s like looking into a financial crystal ball, giving you insight into future payments and encouraging smarter decisions about your finances.

Amortization Methods Unveiled

Exploring Different Amortization Techniques

As you delve into the realm of amortization, you’ll encounter a variety of techniques tailored to different financial scenarios. Let’s explore some of them:

- Straight-Line Amortization: The simplest form, where equal amounts of the asset’s value are expensed each period. If consistency is what you’re after, this method is your steady companion.

- Declining Balance Method: Here, a constant rate is applied to the asset’s declining book value each period. It’s like a snowball rolling down a hill, picking up speed – the expense decreases over time.

- Double Declining Balance Method: A more accelerated version of the declining balance method. It doubles the rate, ideal for assets that lose value quickly in the initial years.

- Bullet Method: This involves a single lump-sum payment at the loan’s end. Think of it as the financial ‘sprint’ at the finish line of your loan term.

- Balloon Payments: Regular payments are smaller, then followed by one large payment to settle the remaining balance. It’s like floating along with a small balloon, then suddenly – boom – a bigger payment pops up.

Each method has its advantages, suitable for different business strategies and financial goals.

Advantages and Considerations for Each Method

Each amortization method brings its unique set of advantages and considerations, tailored to fit various financial situations:

- Effective Interest Method:

- Advantages: The method aligns better with asset usage, especially when benefits from the asset decline over time. It provides a more accurate allocation of interest expense.

- Considerations: It’s more complex to calculate, requiring recalibration if the interest rate changes.

- Straight Line Method:

- Advantages: With simplicity at its core, this method offers consistent amortization expense throughout the asset’s lifespan, making financial forecasting more straightforward.

- Considerations: It might not accurately reflect the pattern of economic benefits derived from certain assets, generally suited for ones with evenly spread benefits.

For the best fit, consider the nature of the intangible asset, the pattern in which the economic benefits are consumed, and the company’s accounting policies.

Practical Application: Amortization Journal Entries

Recording Amortization on Financial Statements

When you record amortization on financial statements, you’re essentially capturing how much of an intangible asset’s value has been used up during the period.

Here’s how to do it:

- Income Statement: Each accounting period, you’ll record the amortization expense. This reduces the income because it’s recognized as a non-cash expense, decreasing net income for the period.

- Balance Sheet: On the asset side, intangible assets are listed with initial costs. As amortization accumulates, it’s recorded contra to the asset’s cost, reducing its net book value.

- Cash Flow Statement: Although amortization is recorded as an expense, it’s added back to net income on the cash flow statement under operating activities since it’s a non-cash expense.

Accurately recording amortization is crucial because it impacts the financial and tax reporting. It doesn’t affect cash flow directly but does influence reported earnings and assets’ values, which investors and creditors scrutinize closely.

Managing Amortization of Assets in Business Operations

When you’re managing amortization within your business operations, remember it’s all about the strategic spread of an asset’s cost over its useful life. Here’s how to handle it effectively:

- Integrate amortization expenses into your budgeting and financial planning. This will help ensure your reports reflect the true cost of doing business.

- Regularly review the amortization schedule against actual asset usage. Adjustments may be needed if the pattern of benefits derived from the assets shifts.

- Incorporate amortized cost data into your accounting software. Automation can reduce errors and free up valuable time for analysis rather than data entry.

- Communicate with stakeholders about how amortization affects profitability and cash flow. Clarity here can inform investment and operational decisions.

- Finally, cross-check the impact of amortization on compliance with debt covenants. Lenders often place restrictions based on financial ratios that amortization can affect.

Embedding these practices into everyday operations can help maintain financial health and navigate the complexities associated with intangible assets.

Advanced Insights into Amortization

Navigating Negative Amortization Scenarios

Navigating the choppy waters of negative amortization requires caution and foresight. In such scenarios, each payment is less than the interest charge on the loan, causing the outstanding balance to increase rather than decrease over time. This typically emerges from adjustable-rate loans or certain mortgage products with flexible payment options.

To steer clear of these tricky situations, it’s advised to:

- Always read the fine print and understand the loan terms, especially the prospect of rate adjustments and payment caps.

- Make larger or extra payments whenever possible to avoid the buildup of unpaid interest.

- Monitor your loan statements diligently to catch any signs of growing debt.

By keeping a vigilant eye on loan terms and payments, you can prevent your debt from swelling and ensure it consistently trends downwards.

Legal and Tax Implications of Amortization

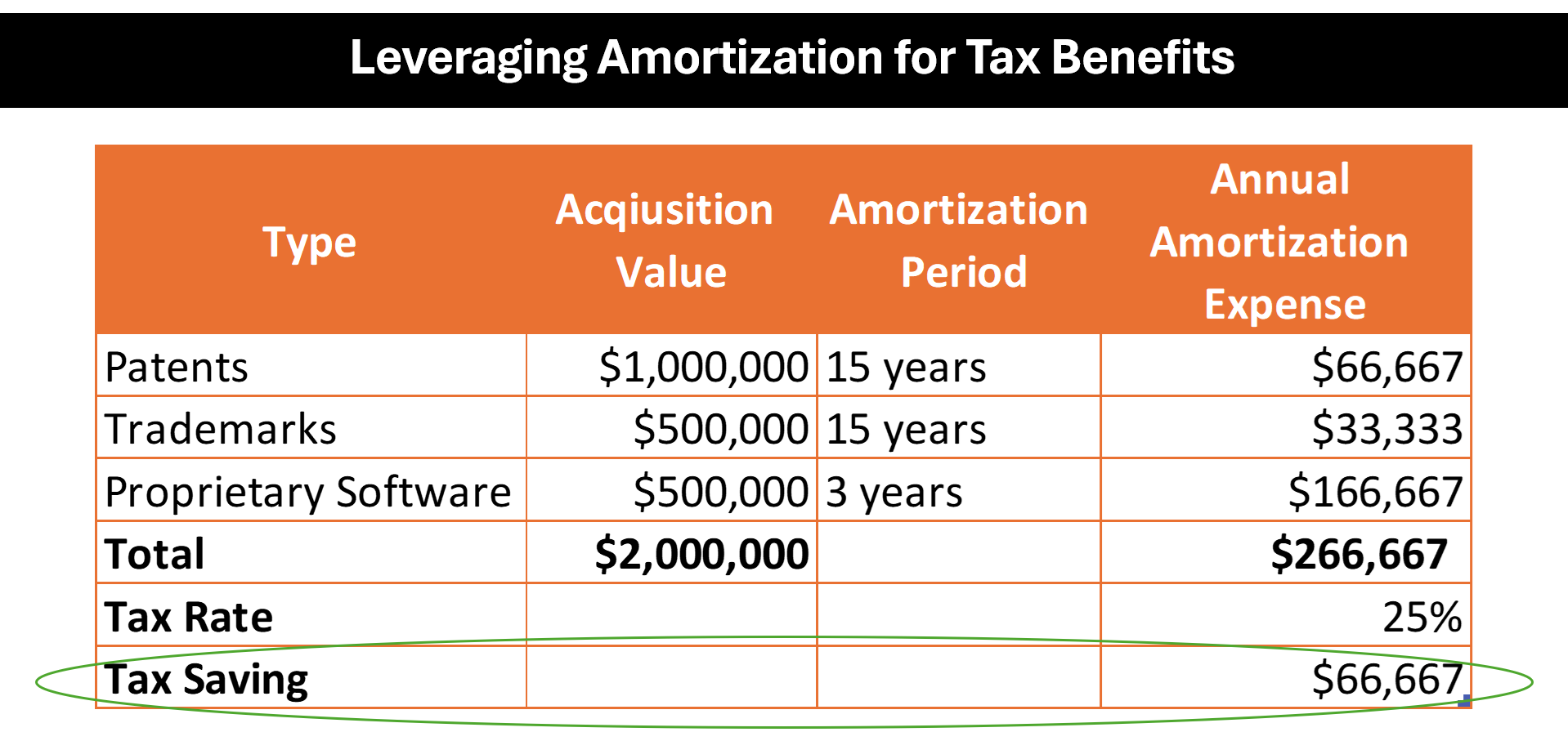

The legal and tax landscape of amortization is marked by nuances that can have significant implications for your business. On the legal front, compliance with accounting standards and regulations is crucial to ensure the fairness and accuracy of financial reporting.

From a tax perspective, amortization can be a double-edged sword:

- It offers tax deductions as the amortization expense is deductible when calculating taxable income.

- However, tax regulations are strict about what constitutes an amortizable asset and how to determine its useful life.

Remember, tax savings today can lead to deferred tax liabilities down the road. So, always work closely with tax advisors to align with the latest laws and optimize tax positions.

FAQ: Addressing Common Queries on Amortization

What Is the Most Common Method of Amortization?

The most common method of amortization is the straight-line method. It’s preferred for its simplicity and ease of calculation, as it spreads the cost of an intangible asset evenly across its useful life. This method provides consistent annual expenses, making it clear and predictable for accounting purposes.

How Does Amortization Affect a Company’s Financial Health?

Amortization affects a company’s financial health by reducing its taxable income since it’s recorded as an expense. This can lower tax bills and affect profits on the income statement. However, it’s also a non-cash expense, so it doesn’t affect the company’s cash flow directly—allowing for a more accurate representation of cash-based operations.

Can Intangible Assets be Amortized Indefinitely?

No, intangible assets cannot be amortized indefinitely. They are typically amortized over their useful life, which is the period over which they are expected to provide economic benefits to the company. Intangible assets with an indefinite useful life, like goodwill, are not amortized but are periodically tested for impairment.

How to understand whether to amortize or depreciate an asset?

To decide between amortization and depreciation, first determine if the asset is tangible or intangible. Tangible assets like machinery are depreciated, while intangible assets like patents are amortized. Then, assess the asset’s useful life; if it’s finite, it’s likely to be amortized. Always adhere to relevant accounting and tax regulations for proper categorization.

What is the maximum number of years for amortization?

The maximum number of years for amortization often hinges on the asset’s nature and the applicable tax or accounting rules. For tax purposes, many intangible assets under the U.S. Internal Revenue Code (Section 197) are amortized over 15 years. However, other assets may have different useful lives as per financial accounting standards or other sections of the tax code.